We feature each fortnight Nicholas Reid's reviews and comments on new and recent books.

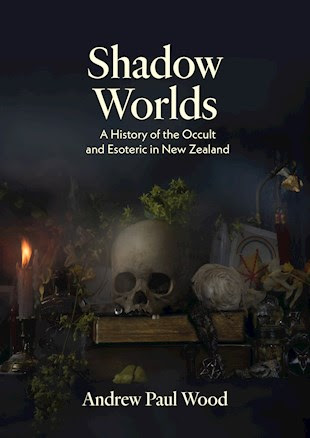

“SHADOW WORLDS: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand” by Andrew Paul Wood (Massey University Press, $NZ55) ; “AT THE SHORT END OF THE SONNENALLEE” by Thomas Brussig [translated from the German by Jonathan Franzen and Jenny Watson] (HarperCollins 4th Estate, $NZ 25:20 paperback)

I’ll begin this review with a clear verdict. Writing about “alternative” cults and religions in New Zealand, Andrew Paul Wood is both respectful and sceptical. He categorises as occult and esoteric all the (most often small) groups that propose spiritual and religious ideas outside New Zealand’s mainstream (the mainstream being mainly Christianity, but also Judaism, Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism). Wood concedes that some occult and esoteric groups have been harmless, and indeed some have contributed to the common good. But he is also aware of a malign streak in certain occult and esoteric groups, especially those that have promoted racism or white supremacism. Wood is critical of what is patently fraudulent or fabricated in some groups, many of which draw upon claims of ancient wisdom which have in fact been concocted very recently. He also calls out the charlatans who have misled their own congregations. As a piece of scholarship, Wood’s Shadow Worlds is very thorough, covering many groups (some of whom you have never heard before) and built on close research. In other words it is an admirable piece of work and contributes much to an understanding of New Zealand history.

Given that Pakeha came to New Zealand little more than 200 years ago, it is inevitable that Wood has things to say about Pakeha misunderstanding and misinterpretation of Maori beliefs and religions. Vigorous attempts were made by missionaries and government to stamp out tohunga and at the same time many Maori adopted syncretic religions, mixing Biblical stories with Maori lore. However Wood’s focus is not on these, but on the esoteric systems that were brought by (and for) colonising Britishers. His introduction advises us that “occulture” in the 19th century was very much a reaction against materialist Enlightenment thought and industrial modernism. There was a feeling that magic and enchantment were being drained out of the world. Thus in the 19th and early 20th centuries, a number British settlers, while still professing to be Christian, embraced Freemasonry, Gnosticism in its various forms, Theosophy, Anthroposophy, the Golden Dawn and other occult systems.

Beginning with Theosophy (Chapter 1) and its first promoter Madame Blavatsky, Wood declares that it “offered a heady cocktail of spiritualism, reincarnation, lost continents and Eastern metaphysics attractively packaged for Western tastes” (p.31). It flourished in Victorian New Zealand in part because one could keep one’s religion, Protestantism, while also adopting pseudo-Hindu and frankly early “science fiction” ideas of what the Cosmos was. Not that all Protestants agreed with this. When an Anglican minister was ordered back to England because he had joined the Theosophists, he was able to retain his status as a member of the Anglican clergy. Says Andrew Paul Wood “The more cynical might argue that Theosophy and the Church of England were actually quite similar in that neither required you to believe in anything at all.” (p.64) Yet many of the great and the good, such as Edward Tregear, became Theosophists, and some of them promoted a more enlightened form of education.

Not as influential, indeed very small in numbers, were the adherents of the pompously entitled Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (Chapters 2 and 4) which – along with Rosicrucianism – was devised from forged and hoaxed documents purporting to be of ancient antiquity. Back in Britain some eminent literary people, such as W. B. Yeats, had joined the Golden Dawn. In New Zealand the cult was most popular in the 1890s, and once again some eminent public figures were initiated. A Temple of the Golden Dawn was built in what is now Havelock North, which seems to have been a magnet for esoteric groups at that time. However the Golden Dawn split and withered away when an American broke from it and set up his own Builders of the Adtyum, emphasising prophecy by tarot cards. In turn, this morphed into the Higher Thought Temple which stood on a prominent street in Auckland until it was sold off in 2014 “due to diminishing adherents”.

Later came to New Zealand the Swiss Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy. As Wood correctly notes, Steiner’s system has in the last few decades fallen into some ill repute, in that there is a clearly racist undertone in much of Steiner’s writing – like so many of his era, he categorised the worth of human beings according to a hierarchy, with white Europeans at the top. Yet at the same time, many of Steiner’s theories on education were very progressive and are still embraced as a model by many teachers. The fact is that Steiner’s more esoteric teachings are now disregarded while there are still many Steiner schools in New Zealand (and elsewhere). This seems to be a case where a movement has tacitly ditched its original esoteric teachings while preserving something practical and useful. In a very limited sense only, a parallel could be drawn with Freemasonry, which had [and has] esoteric rituals purporting to be of great antiquity, but whose members basically treat it as a fellowship and supporter of public enterprises.

From the 1890s to the 1920s there was in New Zealand, as in Britain and elsewhere, a fashion for Spiritualism. Along with séances, ectoplasm (i.e. regurgitated cheese cloth) and Ouija boards, the great attraction of Spiritualism was its claim that devotees could contact the dead. The movement flourished during and after the First World War when there were so many grieving over those who had been lost in battle. Spiritualism became registered as a church in New Zealand in 1923 and it still survives, albeit now with diminished numbers. However the movement was not helped by the visit, in the 1920s, of the convinced Spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The creator of the most rational and evidence-based fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, was himself extraordinarily gullible. Conan Doyle fell for the notorious Cottingley Fairies hoax (later admitted to be a hoax by the young hoaxers) and in New Zealand he showed his audiences “spirit photographs” which audiences readily realised were simple double-exposure trickery. Newspapers and most audiences laughed. Of Conan Doyle, Wood writes “It is unfortunate, perhaps, that the author lacked his celebrated creations’ perspicacity and deductive skill.” (p.200) And yet Wood does note that, for all their mummery, Spiritualists had a good record of being involved in promoting women’s suffrage, campaigning for prison reform, and petitioning for free schooling. He concedes that in its recent version “Spiritualism New Zealand, with its focus on healing, personal responsibility, karma and universal brotherhood, is an earnest force for good in the world” (p.218). However, he then moves into the charlatanism of the notorious TV series Sensing Murder in which mediums cruelly raised people’s hopes by claiming to be able to solve murders (which in fact they were never able to do).

More recent, and having less impact, have been Rosicrucianism and The Order of the Temple of the East, both essentially anti-Enlightenment and anti-Modernism, gnostic in their teachings, and having their origins in 18th century German mysticism although, like so many esoteric movements, Rosicrucians like to believe their origins are from ancient times.

In the course of his wide survey, Wood chronicles some movements that had very limited impact and fizzled away in short time. There was, for example, an inter-war group called the Empire Sentinels, which seems to have been little more than an imitation of the Scout movement, but with some magic thrown in. It didn’t last. The funniest story (in Chapter 6), set in Christchurch in the 1890s, concerns a Temple of Truth, a formidable building run by a self-made American prophet who at first attracted big audiences until he was exposed as a multiple bigamist, an embezzler and a man with a long criminal record in his country of origin. So-called Druids barely took off the ground in New Zealand. [Like so many esoteric movements their beliefs, far from being of ancient vintage, were of recent concoction. – for the genesis of modern Druidry, see Professor Ronald Hutton’s Blood and Mistletoe, reviewed on this blog]. There were also groups that claimed to be building their beliefs out of science. As told in Chapter 9, Herbert Sutcliffe, in the mid-20th century, taught something which he called Radiant Living. Andrew Paul Wood basically gives it a clean bill of health, as the Radiant Living movement mostly concerned itself with exercise, eating healthy food and promoting outdoor living. There was a little mysticism throw in, and cranky predictions concerning the weather, but on the whole it did no harm. Famously, the young Edmund Hillary was a member of Radiant Living.

In a chapter called “The Age of Aquarius”, Wood gives a general survey of the explosion of new cults that came in the 1960s, with communes, cliquey little travelling theatrical groups like BLERTA and Red Mole, Hari Krishna, Moonies, Scientology, mind-bending drugs – indeed a veritable deluge landing on younger people who turned away from mainstream Christianity but who still wanted to cling to something. Wood largely passes no judgement upon these groups, most of which have now faded from prominence.

Wood does however spent much time (basically Chapters 8, 11 and 13) on neo-Paganism, Satanism and Witchcraft. The influence of Aleister Crowley and his “Thelema” mysticism (“Do as thou wilt is the whole law”) gained much notoriety in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, but there was very little with connection to New Zealand. There was the odd person of New Zealand birth who claimed to be a witch, such as Rosaleen Norton who spent nearly all her life in Sidney. The exhibitionist Lorna Jenks, who rebranded herself “Anna Hoffmann”, hung around Auckland in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and she may or may not have dabbled in the occult. Some immigrants from England tried to promote Morris Dancing as a connection with pre-Christian paganism. Then there was the mode, especially appealing to some feminists, for Wicca, a witchcraft which purported to be reinvigorating ancient feminine power and authority. In reality, the beliefs and rituals of Wicca were all devised in the 1950s by the American Gerald Gardiner. More challenging, however, and certainly more unsavoury were the masculine cults, popular among some Pakeha gangs, which adopted a bastardised version of pagan Scandinavian mythology and taught white supremacism. As Wood notes, in Germany’s Nazi era, Scandinavian and German mythology was misused in the same way to promote the idea of racial superiority. The Pakeha gangs were following the same song book. As for out-and-out Satanists, they seemed to come in two varieties: those who used Satanism to ridicule or irritate Christians and those who really believed in Satan as a sort of alternate god. Wood says wisely: “Neopagan revivalism is, for the most part, a pastiche founded in a quasi-anthropological approach to extant cultural mythology and folkloric traditions, whereas Satanism’s source material is almost entirely based on literary fiction, historical hoaxes and theological calumnies.” (p.352)

Very well researched and informative as it is, there are some passages that are heavy reading. As another reviewer has already noted, Wood does have a tendency to give us all the details, not only of figures who are directly relevant to his narrative, but also of the people who were simply related to these figures. It is almost as if he couldn’t jettison some of his scrupulous research, even if it was irrelevant. I am of course carping here, as this is only a slight blemish on a very interesting book.

I must also add some closing comments. Arthur Conan Doyle was a very intelligent man, yet he fell for the nonsense of Spiritualism. W. B. Yeats was undoubtedly a great poet – one of the 20th century’s greatest – yet he too participated in nonsense, the Golden Dawn… as did quite a number of eminent fin de siècle literati. Of course Wood is right in noting that much of 19th and 20th centuries esoteric movements sprang up as a revolt against science, materialism, modernity and the Enlightenment. But I have an added suggestion. Many (not all) occult and esoteric cults appealed to people of the upper crust or those who aspired to be in the upper crust. This was particularly true of the Golden Dawn. It didn’t exactly attract hoi polloi. Its members were well-to-do and perhaps hoping to become a new sort of aristocracy. What was being promoted here was exclusivity – the comforting feeling that the unwashed were not included. This, by the way, was made explicit in Yeats’ pamphlet “On the Boiler”, where he suggested that those dumb Irish Catholic peasants should be put back in their place and the country should be ruled by an elite. To be exclusive, to be part of an elite, to know something [esoteric] that the general public didn’t know – such snobbery was the inspiration of many an occult movement. The mainstream churches were too open to the public and too open about what they taught. They were not elite enough.

Andrew Paul Wood has enlightened me about many things. I thank him.

Personal Footnote: With some pleasure, I note that the first name mentioned in this book is one of my elder brothers, Bernard Reid, who died two years ago. On his opening page, Wood remarks that he may deal with magic but “I do not mean magic in the sense of conjuring tricks, but for an excellent history of that in Aotearoa, consult Bernard Reid’s Conjurors, Cardsharps and Conmen. ” (p.14). For the record, for many years Bernard was a professional magician and illusionist, working in the United States for much of his career. I can fairly say he was regarded highly by the Magic Circle, who are, of course, professional magicians who are sworn not to make public how they perform their tricks. I personally enjoy good magic shows, always seeing them as a battle of wits – aware that it is trickery, will I be able to work out how a trick was done? I have no skills whatsoever as a magician. One thing I learned quickly from Bernard is that most professional magicians tend to be anti-religious and scornful of esoteric cults. Bernard certainly was. Much of this has to do with magicians’ understanding of the trickery involved in such esoteric groups as Spiritualism. One of the last conversations I had with Bernard was where we were trying to puzzle out how such an intelligent man as Arthur Conan Doyle could believe in fairies and “spirit photographs”. I must get around to reviewing on this blog Bernard’s Conjurors, Cardsharps and Conmen.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

It’s very rare to come across a novel that is at once very funny and extremely sad. Thomas Brussig knows what sad is. He grew up in East Germany – the Communist “German Democratic Republic” which fell apart in 1989 when the Berlin Wall was toppled. The Communist state was totalitarian, restrictive, censorious, feeding Communist ideology to school children and adults alike and of course filled with the Stasi, the local spies whose business was to seek out and punish anyone who uttered the least peep against the regime or said anything in favour of the West. When this state eventually fell apart, it was calculated that one in every seven citizens had been suborned to spy for the Stasi. Nobody could ever be sure which neighbours were reporting to the Stasi.

So how could such a state be seen as funny? Simple. Thomas Brussig focuses on a bunch of East German teenagers, in the early 1980s, living in the Sonnenallee (“Sun Street”), a street right next to the Berlin Wall and its formidable armed guards, traps and barbed wire to prevent people escaping to the West. While going through the motions of adhering to the Communist regime, saying by rote the slogans they have been taught and marching in approved displays, the teenagers know how to get around it all with a hearty subversion and a code of their own. And that’s where the fun comes in.

Living in a (typically) very cramped apartment, teenager “Micha” (Michael) hears his parents speculate on which of their neighbours are Stasi – they must be the only ones who get plumbers to come quickly when needed. Micha’s mother dutifully subscribes to the regime’s official newspaper, not because she reads it but because she wants to display her loyalty to the state, even though she doesn’t really believe in it. Micha knows how to dodge or hoodwink the “Designated Precinct Enforcer”, that is, the plainly stupid official thug who monitors everybody in the apartment block. Micha knows there are desirable goodies in the West because every so often his uncle Heinz, who lives in West Berlin, manages to come over with what he regards as contraband goods.

But more than anything, Micha is fixated on Miriam, the most beautiful and desired girl in his class, whom all the boys behold enviously. Micha longs for her. Micha believes she has written him a love note, but before he gets to read it a gust blows the letter over the Wall and into the “death strip” where it is forbidden to go on pain of being shot. Micha’s inept attempts to retrieve the letter, and Micha’s gauche attempts to woo Miriam are the fuel of much of the comedy – crushing her toes in a dancing class; watching wistfully as other boys try to pick her up ; seeing a boy from the West dancing perfectly with her. Oh the teenage angst of it!

Of course the other longed-for treasures are banned rock records from the decadent West. Micha’s buddy Frizz makes desperate attempts to get hold of the latest contraband Rolling Stones records, with farcical results. Meanwhile Micha’s other buddy Mario falls in with a red-haired existentialist girl who tries to get him to subscribe to a system of shutting East Germany down bit by bit. Be it noted that these urban kids are contemptuous of more naïve kids from the rural areas who believe ardently any propaganda the regime pumps out. They refer to them as coming from “the Valley of the Clueless, the area where there was no reception for Western television”.

I agree with Jonathan Franzen’s comment in his preface that “the events in the book are a little too funny to be true, its plot turns a bit too neat.” I also agree that, despite their constricted lives, the adult and teenaged characters make up a credible and likeable community, concerned with one another. Humaneness in a horrible situation. And it is very funny.