REMINDER - "REID"S READER" NOW APPEARS FORTNIGHTLY RATHER THAN WEEKLY.

We feature each week Nicholas Reid's reviews and comments on new and recent books.

“DICTATORLAND – The Men Who

Stole Africa” by Paul Kenyon (Harper-Collins, $NZ37:99)

Sometime ago I took the opportunity to review, in the

“Something Old” section of this blog, Chinua Achebe’s famous novel Things Fall Apart. I remarked then that

nearly all the books I’d ever read about Africa were not written by Africans.

That included Martin Meredith’s very depressing The State of Africa [also reviewed on this blog], published in 2005.

Meredith chroncled in awful detail the dictatorial regimes that have dominated

and oppressed most Africans in the last fifty years. So appalling was much of

the detail that, I said, I ended Meredith’s book being grateful that I lived in

a country where at least the rubbish is collected.

Sometime ago I took the opportunity to review, in the

“Something Old” section of this blog, Chinua Achebe’s famous novel Things Fall Apart. I remarked then that

nearly all the books I’d ever read about Africa were not written by Africans.

That included Martin Meredith’s very depressing The State of Africa [also reviewed on this blog], published in 2005.

Meredith chroncled in awful detail the dictatorial regimes that have dominated

and oppressed most Africans in the last fifty years. So appalling was much of

the detail that, I said, I ended Meredith’s book being grateful that I lived in

a country where at least the rubbish is collected.

Paul Kenyon’s Dictatorland

covers similar territory, but it is not as inclusive as Meredith’s history. A

British journalist, Kenyon joins general history with anecdotes based on his

own travels in Africa. Dictatorland

therefore veers in style from pages based on earnest historical research to

more chatty and personal observations, sometimes with slightly jarring results.

Kenyon has also decided to organise his text thematically, rather than giving a

general survey of the state of the whole continent. His theme is the resources

of Africa, and how they have been exploited (or squandered). In his

introduction, he considers what he regards as the most significant natural

resources of Africa. So he divides his text accordingly into three parts: (1.)

Gold and Diamonds; (2) Oil; (3) Chocolate…. with an uneasily added fourth part

about the slave trade. This means that he deals only with those dictators who

have been related to these commodities, so readers should not be surprised that

some of Africa’s most notorious tyrants figure only in footnotes or not at all.

There

is a major problem when a European broaches the topic of indigenous African

tyranny. It can easily encourage the racist view that Africans are not capable

of ruling themselves. Although he is dealing with grotesque misrule by Africans,

Kenyon nowhere encourages such an idea. He prefaces each chapter with a

backstory showing how African resources and African peoples were exploited by

the old European colonial powers (Britain, France, Germany, Portugal et al.).

Those powers left a legacy of unstable states which often yoked together

incompatible tribes, and therefore set the conditions for strife and power

struggles once independence came half a century ago. Kenyon also shows how

international corporations have been happy to make profitable deals with

Africa’s own tyrants.

Even

so, the focus is on African despots.

We

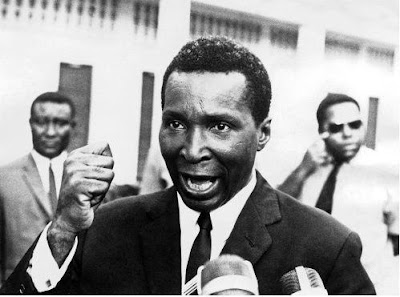

begin with Joseph-Desire Mobutu (or “Mobutu Sese Seko”, as he later rebranded

himself). For thirty years he controlled what has now reverted to being the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, but which Mobutu insisted on giving the

artificial name “Zaire” (a name not accepted by the mass of Congolese any more

than the junta-imposed name “Myanmar” is now accepted by the mass of Burmese).

Having, with CIA and Belgian support, overthrown Patrice Lumumba, who was

clearly the more popular figure at the time of independence, Mobutu set about

ruling a state based entirely on cronyism and self-enrichment. International

corporations paid Mobutu fabulous sums to get the rights to the country’s

mines, but none of the proceeds trickled down to the population. Instead

Mobutu’s Swiss bank accounts became incredibly fat. Mobutu’s much-touted

“authenticity” (supposedly emphasising Africanness as opposed to Europeanness)

was always a fraud, and his attempts to articulate a coherent ideology came to

nothing. As Kenyon remarks:

We

begin with Joseph-Desire Mobutu (or “Mobutu Sese Seko”, as he later rebranded

himself). For thirty years he controlled what has now reverted to being the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, but which Mobutu insisted on giving the

artificial name “Zaire” (a name not accepted by the mass of Congolese any more

than the junta-imposed name “Myanmar” is now accepted by the mass of Burmese).

Having, with CIA and Belgian support, overthrown Patrice Lumumba, who was

clearly the more popular figure at the time of independence, Mobutu set about

ruling a state based entirely on cronyism and self-enrichment. International

corporations paid Mobutu fabulous sums to get the rights to the country’s

mines, but none of the proceeds trickled down to the population. Instead

Mobutu’s Swiss bank accounts became incredibly fat. Mobutu’s much-touted

“authenticity” (supposedly emphasising Africanness as opposed to Europeanness)

was always a fraud, and his attempts to articulate a coherent ideology came to

nothing. As Kenyon remarks:

“He demanded complete obedience to the

official ideology of his newly created party…. But what was his political

philosophy? It was difficult to pin down: generally liberal in economic matters

but almost Maoist in his social control. Anti-communist, but at the same time

anti-capitalist. There were bits and pieces of everything in there, a political

stew into which Mobutu tossed whatever ingredient he chose. He welcomed the continued

support of the US, while at the same time travelling to Beijing for

inspiration. Why not call it Mobutism and be done with it? And so it was, and

just like other personality cults, he needed to strip the country of all that

went before in order to start rebuilding it in his own image…” (p.35)

This

entailed bankrolling such prestige projects as his own version of the palace of

Versailles, while the country’s infrastructure degenerated to a level worse

than it had been under Belgian colonial rule. And, of course, thousands of

political enemies, or perceived political enemies, were imprisoned, tortured

and killed. When the economy of the Congo eventually hit rock bottom, Mobutu

attempted to bolster his international profile by intervening in the war that

was then going on in Angola.

I

couldn’t help feeling a huge wave of Schadenfreude when I at last reached the

page where Mobutu, sitting in front of his TV screen, watched footage of the

Rumanian Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu being overthrown and shot by his

own people; and Mobutu at last realised he could face the same fate. His

subsequent attempts at a charm offensive, to win over his own people, were a

miserable failure. To everybody’s relief, he was overthrown and died in 1997.

Mining

wealth also comes into the next chapter with its story of Robert Mugabe of

Zimbabwe, and his systematic destruction of that country’s economy – not to

mention his strong-arm tactics to suppress or intimidate any legitimate

political opposition. Comparing the post-independence histories of the Congo

and Zimbabwe, I am very struck by the fact that both despots began as close

friends and comrades of people whom they later spurned or destroyed – Patrice Lumumba

in Mobutu’s case and Joshua Nkomo in Mugabe’s case. Both also continued, during

their respective tyrannies, to live off the myth that they were genuine freedom

fighters, thwarted only by capitalist imperialism.

When

Paul Kenyon turns to the matter of oil, he first devotes a chapter to the

shabby deals that British, Dutch and American companies (BP, Shell, Esso,

Caltex) made in the 1950s with Libya’s King Idris, to get as much oil as

possible at the minimum cost. Naturally Idris and his ministers were all

hopelessly corrupt. When finally, in the 1960s, Idris was overthrown by the

handsome young army officer Muammar Gaddafi, there was real hope (as there had

been when Nassar unseated King Farouk in Egypt) that his regime would be a

humane and reformist one. Kenyon notes an iconic photo that was taken of

Gaddafi, just after he had taken over, standing with Nasser in the back of a

Land Rover. He remarks:

“And if the clocks had stopped there, in the

winter of 1969, that image might have adorned a generation of students’ walls.

There could have been silk-screen prints by Andy Warhol, Gaddafi ballads from

Joan Baez, revolutionary anthems from John Lennon. He had driven out the

imperialists and begun redistributing the country’s oil money. There were

promises of modern hospitals and schools for all. But, for those who watched

events more closely, there were already clues as to where all this was heading.”

(p.167)

Where

it headed was, of course, to another closed dictatorship, which in this case

took to sponsoring terrorist movements abroad. The sordid details of Gaddafi’s

regime are notorious enough (mass imprisonment, torture, public executions

etc.). So is evidence of his psychological instability – witnessed in the corps

(or harem?) of young women whom he kept as his personal bodyguard. But once

again some details are so grotesque that they can be greeted only as sick

humour. Take the story of his sons. One paid for a degree at the London School

of Economics, which gave him a doctorate on the strength of a thesis that somebody

else wrote for him. Another fancied himself as a football star. His father therefore

made him captain of the national team. When he performed dismally, the crowd

booed him. So he had the national football stadium bulldozed to the ground. You

can do that if your father has unlimited power.

The

other oil-rich countries with whose dictators Kenyon deals are Nigeria and tiny

Equatorial Guinea.

It

is quite clear that Francisco Macias Nguema, the dictator of Equatorial Guinea,

was literally and clinically insane. He suffered from drug-induced hallucinations

and real paranoia. He was the man who organised a synchronised execution, in

the national stadium, of 150 of his perceived enemies. They were hanged as the

pop song “Those Were the Days” was piped through the loudspeaker system. During

his reign, nearly half Equatorial Guinea’s population fled in terror to safer

countries. Macias was overthrown and succeeded by his nephew, the equally

corrupt Obianga, who is still in power. Kenyon notes that both West (America,

Europe) and East (China) court him for access to his oil.

Nigeria

is a far larger and more complex country. Like Zimbabwe (back when it was

“Rhodesia”), Nigeria was an artificial creation of the British Empire. In

Zimbabwe, the Shona and Ndebele peoples were pushed into one state by the

imperial power. In Nigeria the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and Igbo people were forced

together. Independence led to civil wars and a revolving door of coups and

dictators through twenty years. Every dictator looted the oil revenue which

mainly came from the Igbo region (which had vainly sought to win independence

as “Biafra”). The longest lasting dictator was Sani Abacha who (cue for sick

laugh, please) died of a heart attack after taking three Viagra pills when

trying to service three prostitutes.

As

always, Kenyon draws no racist conclusions from this mess, noting how much

Abacha throve on deals with international corporations who were not in the least

worried by violations of human rights – so long as they could extract the

precious black stuff. Nigeria’s most outspoken advocate for human rights was an

internationally-respected intellectual, Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was eventually

hanged by Abacha’s goons. Kenyon quotes Saro-Wiwa’s caustic comment on foreign

investors:

“We are face to face with a modern slave

trade similar to the Atlantic slave trade in which European merchants armed

African middlemen to decimate their people and destroy their societies… As in

the Atlantic slave trade, the multinational companies reap huge profits.”

(quoted p. 249)

Compared

with mineral wealth – gold, diamonds and oil – cocoa may seem a small element

in this saga. Perhaps it is. I can’t help feeling that Kenyon included his

“Chocolate” section so that he could tell, in a chapter of its own, the woeful

tale of a scandal back in the old imperialist days. In the very early 20th

century, the colonial power Portugal harvested the cocoa crop in its equatorial

possession by what amounted to slave labour. Chief beneficiaries of this were

the British companies Cadbury’s, Rowntree’s and Fry’s, all of which were run by

morally-righteous Quakers who were loudly opposed to the slave trade and noted

for their humanitarian enterprises. But when investigating reporters (one of

whom was hired by the chocolate companies themselves) exposed the conditions of

slavery under which the cocoa harvesters laboured, the British companies were

very reluctant to admit the fact, fearing a boycott of their products. They

successfully sued a newspaper which reported the facts.

Having

got this tale out of the way, Kenyon moves on to consider the dictator of

cocoa-rich Cote d’Ivoire, the Francophone and basically Francophile Felix

Houphouet-Boigny. Compared to other dictators, Houphouet-Boigny (who died in

1992) was relatively benign – at least his form of oppression didn’t amount to

full-scale genocide. He is most notorious for spending billions on having built

a basilica near his home village, vaguely modelled on St Peter’s in Rome, but

far larger. This sort of pointless conspicuous consumption is a feature of most

of the dictators covered here.

The

final chapter of Dictatorland is

poorly integrated into the book. Kenyon switches to Eritrea, to tell the story

of Isias Afwerki, who is still regarded as a nationalist hero by some, because

he fought (successfully) to extract his country fron Ethiopia. But in doing so,

Afwerki militarised his small state to the point where there is universal

conscription and a massive slave trade as young men are, in effect, kidnapped

for sale to the armed forces.

While

this book is filled with enlightening information, I closed it with the sense

that Kenyon has foxed himself in the framework he has chosen. By dealing, in

all but the last chapter, only with those African dictators whose power rests

on marketable natural resources, Kenyon misses out other equally notorious

dictators and self-appointed strongmen (Idi Amin, “Emperor” Bokassa etc.). The

picture is a skewed and partial one. Even so, Kenyon does prove how irrelevant declared ideologies

are to the history of oppression. Outside the megalomaniac designs of the

dictators themselves, the finger can very easily be pointed at international

capitalism, for bankrolling dictators in the interests of controlling

resources. But recently the rival ideology of Marxism has been just as

destructive in Africa, witnessed in the ultra-Marxist slogans both Afwerki and

his Ethiopian enemy Mengistu adopted. The old Soviet Union, the new Russian

Federation and China have been just as eager to get a share of the African loot

as any corporation plutocrat, and have sponsored regimes as brutal as those

bonded to neocolonialism.

As

for the high-sounding ideological manifestos which so many dictators produced

upon taking over their unhappy countries, they proved to be little more than smoke to

cover the ancient vices of greed and a lust for power.