We feature each fortnight Nicholas Reid's reviews and comments on new and recent books.

“STILL

IS” by Vincent O’Sullivan (Te Herenga Waka University Press $NZ30); “IN THE

HALF LIGHT OF A DYING DAY” by C. K. Stead (Auckland University Press $NZ29:99);

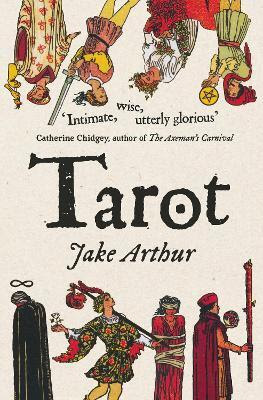

“MEANTIME” by Majella Cullinane (Otago University Press $NZ30); “TAROT” by Jake

Arthur (Te Herenga Waka University Press $NZ25)

Not by design but by happenstance,

three collections on this posting refer to death – Vincent O’Sullivan’s death; the

death of C.K.Stead’s wife Kay; and Magella Cullinane’s loss of her mother… and

even Jake Arthur’s “Tarot” does sometimes refer to death, albeit cryptically.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

New Zealand was deprived of a great poet when Vincent O’Sullivan died,

aged 86, in April of this year. (My tribute to him, Remembering VincentO’Sullivan, can be found on this blog). O’Sullivan was prolific in

his poetry when he wasn’t writing short-stories, novels and non-fiction

biographies. Fortunately, there was one last collection of poetry to be

released posthumously, Still Is. It contains ninety poems,

perhaps because O’Sullivan aspired to reach that age. As always in his

collections of poetry, O’Sullivan does not organise his poems as a series of

themes. His poems are presented in no particular order, and he often makes the

title of a poem part of the poem itself. Given his age, there are naturally reflections

on ageing, and therefore there are also poems calling back the past, including

childhood and adolescence. The first three poems of Still Is consider

vague remembrances of making love (old age recalled); a blind man who can find

his way around (overcoming infirmity); and a refection on gates as they once

were.

Reading this collection, I can’t

help noticing some predominant themes and ideas.

First there is remembrance itself,

tied to the idea of time and of our tendency to misremember events. The ticking

of time is seen in terms of art in the poem “Randomly so, in a gallery” where “Lightens.

Dark comes in. Their grace we go along with, / clocks edging season to

season. / Painters as ever insisting their one belief: / the leaning of

great slabbed light, dark slanting in.” The poem “Last time” begins “It was so different

last time… / There were thrushes. I remember it rained / in buckets. The

tarseal on the drive / crinkled in the torrent. I remember that…” and there

is the persistent idea of how apparently small and apparently insignificant

things can nevertheless be the most remembered things. In remembrance there is occasionally

a reaching back to how forebears were presented to him when O’Sullivan was young. “Slaint” is one of the few poems that deals

with O’Sullivan’s Irish ancestors while “Uninvited twin” also broods on the

fortunes of the Irish who crossed the Atlantic. Inevitably, too, there are

childhood memories with “Grey Lynn Noir” (just avoiding being beaten up by the

local thug), “Bastards, down from the hills” (a very rough boys’ game), “Seven,

yes” (little boy first understanding that “bum” is a rude word… though

grown-ups use it often) and a poem or two referring to attending convent

school. As for early adulthood (when O’Sullivan would have been in his

twenties), the prose poem “To be fair to the Sixties” is about hippie-ish

druggie-ness in the 1960s and suggesting how it was mainly pointless if not

destructive.

As

for old age, there are inevitably reflections on decay. “He comes to mind” considers meeting a solitary old man

and how his stoicism sustains him. “Any

weekday’s likely” basically tells us that all things decay. And there is a more

ironic take on decay with “Catching Lenin’s ear”, about how the

dictator’s preserved body is falling apart.

Speaking

of extreme states of mind, we are presented in a number of poems with how the

brain works. The poem “extras” is halfway

between theatre and halfway a dream when under dental anaesthetic. “Premonition”

combines mental fantasy with suburban unease [it’s in part about spiders];

while “As

few may tell you” is an ironic account of ghosts and how people do or do not

deal with them. Though O’Sullivan was ambiguous about religion, with regard to

his Catholic upbringing he could be amused. He uses the title “This business of

lost belief” not to tell a tale of losing religion, but to tell of missing his

chances with a girl whom he admired when he was a young teenager.

His sometime quirky-ness is found in

“Either isn’t or is” and “Dreamwork” both of which take cats to be arbiters of

life and death – after all, silent cats do appear to be watching and judging us

don’t they? In contrast “Ciao, Norman” is

a brisk but heartfelt elegy for a dog that had to be put down.

These

are just some of the ideas that O’Sullivan dealt with in his last collection.

His

style is various. He could build vivid,

if daunting, scenes, as in “A good place to buy” viz. “The winds hug at the

house till the ribs crack. / The guttering swings loose as a shot arm. / The

sound of shrieking’s in the splitting wood. / The violence you have to accept

before spring / breaks perfect.” He

could be jocular as in “Easy does it, easy” which I take to be an elderly man

accepting that many things which once seemed precious or important but which

now can now be shucked off. I quote it in full: “Dogs on beaches. / Books on

shelves. / A single mirror / For a dozen shelves. / A toy Ned Kelly / A theorem,s

proof / A spinning dolphin / On a garden’s roof. / A wall of photos / Tell a

hundred years, / A funeral’s laughter / A wedding tears. / A life of veerings /

You make out was straight. / Nicely polished granite / And a final date. / Like

hell, we say, / Let’s start again. / The sermon’s over. / The day shines

through rain.”

Then

of course there is O’Sullivan’s ability as a critic. “Confessional as it gets”

politely answers a reviewer who suggested he was out of steam. He confesses: “At

times – yes, I need to say it - / between the sighs of the living and the

vanished / departed, I’ve written jaunty numbers, / turned the wry erotic

lyric, / half a dozen times I’ve persisted, / tasteless even, after dusk…”

But then aren’t such poems necessary to prevent poets from becoming too solemn

about their work? “A gift for drama” notes how much of human interaction as

play-acting… we are like squealing mice. “No choice much, any longer” suggests

there are so many writers now that the same themes are being overworked (all

too true). “So at least we know” sees the broadcast evening news as usurping

communal prayer as “The News an atheist’s variant / on prayer: for what the

day has achieved, / forgive us; from what tomorrow intends, / preserve us; out

of creation’s wreckage, / rise again.” “Life on air, for example” is a

half-jocular, half-mocking of New Zealand radio.

At

a certain point though, O’Sullivan accepts that though we are a special

species, we are still animals. I quote in full his poem “To accept being human”

thus “I give thanks we were cradled in branches, / that we moved on so

surely to hands daubed in caves. / I give thanks to the dragged knuckles / and

the penetrating gaze. I’d be so proud / were Silverback an ancestral name. / I

watch viewers at the rail of the ape enclosure. / I’m at one with ordure

accurately flung.” And he is clearly jocular about the approach of death in

“Nothing too serious, mind you” and “For the obituarist”. These must surely

have been written when O’Sullivan’s was aware that he was dying.

My

apologies for naming and quoting so many of O’Sullivan’s poems but, believe me,

I have quoted less than a third of the ninety. Certainly a man of many

interests. As for the title “Still Is”, I can only see the defiance of a man

who accepts that the world is as it is. There is often a bluntness in O’Sullivan’s

poetry, but it is refreshing when put up against the preciosity of many poets,

too eager to show off their erudition.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

* *. *. *. *. *. *. *

In a preface to In the Half Light of a Dying Day, Karl Stead,

now in his 92nd year, reminds us that he had written poems inspired

by Catullus in earlier collections, one being “The Clodian Songbook”. In the age of Julius Caesar, Catullus wrote many

love poems – or poems of rebuke and annoyance – to a woman whom he called

Lesbia. This woman is now generally understood by Latinists to have been Clodia

Metelli, wife of a powerful general and official. Avoiding the name Lesbia,

Stead uses the name Clodia for the alluring and fickle woman of many moods.

However, in these poems Stead himself takes the role of Catullus. Catullus is a means of

talking about the present as much as the past. In the second part of this

collection, Stead creates a new character

called Kezia, a name used in some of Katherine Mansfield’s stories. If Catullus is Karl Stead, then Kezia is Kay,

Stead’s wife of seventy years, who died in July of last year. While the first

part of In the Half Light of a Dying Day deals with many different

ideas, the second part is focused on the drawn-out illness and final death of

Kay, becoming a long and moving elegy. All these poems were written in 2023.

Part

One is “The Clodian Songbook [Continued]” which begins with a

general invocation, then turns to “History”, an account of the precarious times

in which Catullus lived, invited to a banquet with Julius Caesar when he had

written smutty poems about Caesar’s circle and could have been killed for it.

But while others were killed for mocking, and Caesar himself was killed,

Catullus’s main punishment was to be unknown for centuries. Catullus died when

he was thirty, and only the “silence of the grave / and with the passage of

so many centuries / your words and your wit would / find their way home.”

With “The Farm” Stead injects New Zealand images and “Moreporks”

into a story of Stead /Catullus as a boy. Kevin Ireland is addressed as the

Roman poet Licinius in a “shape poem” that welcomes him as a comrade. But in

another “shape poem” Stead takes a crack at James K. Baxter as “Hemi

/ shaggy and barefoot / he was your Diogenes / full of contempt for your wants

and your wages / and with a wisdom not all his own - / traditional, Catholic /

not entirely to be sneezed at / but for Catullus / retrograde / masculist / at

once flashy and necromantic / belonging to a past / best left behind.” He

concludes “Catullus envied your fluency / Jim / but thought you might have

put it / to better use.” There are poems that seem to be aimed at an

in-crowd which would not be understood by us outsiders. “Creative writing

class?” appears to be about a rupture between poets, but who were they?

“Uncertainty” has young Stead/Catullus at a bohemian gathering trying to guess

“who among us is fucking whom”. There is an apocalyptic piece

about the “World’s End”, though without being hysterical and “The good man in

love” wherein Catullus pleads with the gods that he be shorn of any love for

Clodia given that she was untruthful, unfaithful to him… and yet he still can’t

break away from her. Now that is a theme that is brushed earlier in a version

of Catullus’s famous epigram “Odi et Amo” – “I hate and I love” - still attracted to Lesbia [Clodia] but

still appalled by her. [For the record, and standing outside Stead’s poetry,

I note that in full Catullus’s epigram reads “Odi et amo, quare id faciam,

fortasse requires? nescio, sed fieri sentio et excrucior”. The best

translation I have ever seen is in James Michie’s translation of all Catullus’s

work, thus “I hate and I love. If you ask me to explain / The contradiction,

/ I can’t, but I can feel it, and the pain / Is crucifixion.” ] How

much do Stead’s Catullus poems refer to his love life? I’m in no position to

know.

Part

Two “Catullus and Kezia” is very personal in its presentation and

therefore difficult for an outsider to discuss fairly. Stead opens with “Home”,

in which old man and old woman are no longer travelling “no more travel for

them…/…old age has taught them / to love what they have / this green enclave

where flowers and fruit flourish / where tui and blackbird, / pigeon, sparrow

and thrush / build / and teach their young to fly”. Perhaps this is an

idealised version of the Steads’ Parnell home, but it leads into happy memories

when husband and wife were young. “Language again” gives a [possibly] idealised

version of their first love-making. But the sickness of Kay is looming.

“Modern Miracles” is an ironic title as the poem

concerns the way modern airlines could whisk the Stead’s younger daughter back

from London when Kay’s health was declining. Starting with the poem “Free will”,

the couple do some intense thinking about their lives. Karl’s wife of seventy

years says she chose to stay with him, despite all their ups and downs…

They consider photos of themselves when they were young… and how her absence

from public places is now being noticed by friends… and the importance of her

reading. But the physical decay is relentless. The poem “Pain” considers “the

gods” who are silent while Catullus / Karl tries to ease the pain of Keyzia / Kay by rubbing

her back “she panting, shivering, sweating / seeming so small so shrunken

and depleted / and still so loved.”… And finally in “Sorry”, the tragic

moment comes when Kay dies beside Karl in their bed. “You kissed her cheek / Catullus / and told her

you were sorry / and wept. / She would have wept to see you weeping / but could

not / did not know they were your tears / falling on her face / did not know

anything / anymore / who had known so much.”

There

is the long aftermath. In “The science” he longs for, but cannot embrace, the

idea that there is something after death. Then there are reveries: In “Gallia”

he remembers the pleasure of being together with Kay in southern France; and

Paris. There are briefer poems almost nearing the epigrams of [the real]

Catullus - “The plum tree”, about life still going on when he is still

alive (and now wearing a Medic Alert).

With “A Beginning” he remembers when they had their first child, in the early

1960s. The poem “Now more than ever seems it rich” picks up on John

Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”. Keats continues “Now more than ever seems it rich to die, / To cease upon the midnight with no

pain, / While thou art pouring forth thy

soul abroad / In such an ecstasy! / Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in

vain— / To thy high requiem become a sod.” Catullus

recalls Kezia calling for this poem and weeping at the beauty of it… but Keats’

harsh word “sod” suggests immediately the finality of death. “The wound”

appears to refer to the poet’s love life and his wife’s reaction to it. Kezia

says that Catullus’s poems about Clodia “had to be written / because of your

deplorable / romantic ego / and the wound it had sustained”. Of course there are other

interests that intrigue – “The Story?” suggests that high culture as we know it

is collapsing ; “The puzzle” has him recalling his childhood and how very

different Auckland then was; “Catullus demonstrates a vulgar taste” when he

watches on his own, and thoroughly enjoys, the old song-and-dance movie “Singing

in the Rain” (and so he should, dammit). And inevitably “After death” is the

closing poem. The final words are “in the half

light of a dying day”.

I have to close with the

most obvious words – the “Catullus and Kezia” sequence of this

collection is by far the more engaging, and I would also suggest the more

heartfelt, of the two sequences. It is a genuine elegy and it would have taken

great devotion to write it.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

Back in 2018, I had the great pleasure of reviewing Majella Cullinane’s

debut poetry collection Whisper of a Crow’s Wing (reviewed - all too

briefly – on this blog

). Irish-born and raised but now New Zealander, Cullinane’s style was described

by me thus: “It combines a romantic sensibility with a modernist

sharpness.” Cullinane dealt with Irish old times and emigration and her own

Irishness, all with an excellent sense of time, place and perspective. In

Meantime, she has a much more testing perspective to deal with. I take the collection’s

title to have a double meaning – “meantime” usually means filling in time; but

here the time really is mean. When Covid 19 was shutting New Zealand down, and

travel was restricted, Cullinane’s mother, far away in Ireland, was succumbing

to dementia. Even by long-distance phone calls, Cullinane had great difficulty

talking to her mother who became more incoherent as her dementia increased.

Cullinane charts this trying and

tragic situations in three parts.

Part

One “Am I still here?” begins with the poem “This is not my room” – the

poet’s mother refusing to stay in the hospital that is caring for her and

already confused as to whether she is still at home. The mother is also very

much aware of a world beyond this earthly world – a mixture of Christianity and

folklore. In “The believer” she shows her awareness of the dead [as told by the

daughter]: “They’ve been calling you more of late. They, who can’t be seen

or verified. / For a believer, it’s hard to ignore the dead, or that other

world / most can scarcely reckon with, the one you’re so certain of.” In various poems, the mother imagines noises

in the hospital. She thinks of supernatural beings. She is sure a French angel

is visiting her… and she has forgotten her wedding day. But we are aware that

we are seeing all this through the eyes of the daughter, far away in New

Zealand. It is the daughter [the poet] who has to imagine her mother’s

reactions in “If the walls could speak.” And then we come to the definitive point,

“The long goodbye”: “They call what’s

happening the long goodbye - / the

disease that each day snatches parts of you / and scatters them about, until

you can’t find them, / until you don’t remember losing them.” This is the

painful process which every carer knows – the time when it is clear, in the

patient’s loss of memory and inability to do routine things, that dementia is

irreversible.

Part

Two “Meantime” has the daughter coping with her mother’s death and also

her sense of guilt that she has not been able to attend her mother’s funeral.

When the mother has lost communication, the daughter delves back to childhood

and the family’s rituals. The poem “The wedding ring” reads in full

“My sister removed your grandmother’s wedding ring, gripped / your calloused

palm, took your cold hand in hers, / the same hands that held us, the arthritic

fingers / that once kneaded bread, the long fingers that never glided / across

a piano keyboard, never strummed the strings of a guitar.” “Virtual

funeral” forces the daughter having to guess what her mother’s funeral was

like, as she is torn by her absence on the other side of the world: “On the

morning of your burial, it’s late evening here. / Everyone’s in bed, the house

is quiet. / I’m in the sitting room, lying on the couch / waiting for the call

from my sister. / She tells me she feels better now that you are safe.” In

“Meantime” she still has a sense of guilt for her

absence “I would compress seas and oceans, turn hemispheres upside down / to

believe what has happened has not happened…. /… I try not to think of you in

the spring-churned earth, far away so cold in there so cold.” She creates poetry inspired

by Dante, especially “Make no sound” has her questioning “why are we in

purgatory? Wasn’t her mind purged enough?”. She experiences the huge sense of loss as she sees momentarily a

woman looking like her deceased mother.

Part

Three “Nowhere to be” finally brings some sorts of closure. There is in

this last section, the long-term regret, remembering mother (and father in the

poem “Widower”) and their Irish home… even if the poet is triggered by things

she sees in New Zealand. She has many dreams of her mother, now seen in her

mind as younger than she was in the end. The daughter remembers in detail some

of her mother’s skills, such as making bread. The poem “All Souls” is halfway

to belief in the traditional All Souls (remembrance of the dead); and

“Something to say” has the poet, who rejected her mother’s beliefs and

religion, now understanding their power more. “Stay here” has her calmed by

nature, by walks… and all the time wishing her mother was with her: “Could I

tell you the cat followed me to the shops / but I didn’t notice until I met her

on the train tracks / as I was coming home? You would have laughed. / Could I

tell you I wish you could see this sky? / We could sit on the deck. / Ignore

the overgrown clematis – I’m not much of a gardener. / I wish I could speak to

you / but I don’t understand the language of the dead.” In a sort of coda,

she visits the Old Country and says goodbye to her mother’s grave.

I

apologise for this half-baked excuse for a review. As you will have noticed,

all I have done is to give you an account of Majella Cullinane’s ordeal, presented in three segments – mother’s

infirmity and mental decline ; mother’s collapse and death ; daughter’s regrets

and conciliation with memories and the present. What I have not dwelt on is the

clarity of Majella Cullinane’s style. Regrettably, clarity is a rare virtue in much

current poetry. Cullinane’s style is

lyrical when it has to be, straightforward when it has to be, and always fully

aware that there are many different but valid ways of embracing this world and

what might be beyond it. Meantime hangs together as one coherent

statement and proves Cullinane’s outstanding skill as a poet.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

Last year (2023) Jake Arthur

produced a brilliant debut with a collection of poetry called A Lack of GoodSons (reviewed on this blog). It dealt with many

psychological states, often referring to chronic mental discomfort. Though

mainly written in the first person, it was not necessarily confessional.

Arthur’s new collection Tarot often deals with some of these same ideas,

but the approach is very different. The opening quotes Hamlet: “What

should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven?” - which is

virtually a cry of despair, a man’s horror at the state of things and the

crushing littleness of the self.

This time, the conceit (presented in

the opening poem “Querent 1”) is that a Tarot reader is reading the cards to a

callow listener who is apparently male. Given the Tarot cards, there is in what

follows much symbolism, the imagery sometimes tending to the medieval. The title

of every poem is connected to a Tarot image - “Knight of Swords”, “Seven of

Cups”, “The Wand” etc. I do not know how seriously Jake Arthur takes the Tarot,

but it is at least a framework in which conditions and states of mind can be examined.

And one idea that is examined frequently is the nature of the sexes, and the

friction between male and female. Male and female both speak through the cards.

“The Spell” appears to be concerned with ambiguity about sex or gender. “His

Mien” begins “No accounting her taste / For hangdog men, weak / of chin and

short of smiles, / Not so much brooding as broken, / And if he’s good in the

bedroom / No one wants to imagine it.” This is at least a sad perspective

on ageing, but it introduces the idea of women as domineering. “Rest and

Recreation” has a dominant woman sexually using a man and having somewhat

patronising ideas about him. In “Play-time” a distraught woman appears to be

planning arson.

Is this misogyny? Probably not, for these poems could also be

read legitimately as a young male groping to understand the nature of women.

And there are some poems, such as “Mater familias”, in which a mother is

celebrated, even if in a wry way. “Her Caller” and “Salt” appear to be

childhood memories.

As for the male, there is much

admiration. “Lost bantam”, the longest poem in the collection, begins as a

story of being shipwrecked and washed ashore on a desert island, but morphs

into a tale of gay desire. “Goose” is the most overtly gay poem in the

collection, while “Tagus”, a poem about Alexander the Great, suggests masculine

comradeship which is much more than just virile.

It’s

important to note that while Jake Arthur is concerned with the sexes, he also

has many other interests. “Life Hack”, pessimistic in the face of ecological collapse, he suggests it might be

best for us to get used to it and again lived simply as our mediaeval peasant

ancestors did. “Re-gifted” is perhaps the most desperate poem, about an

over-intelligent kid who grows up to find his intelligence means nothing. Grown

up, the kid says “I was one of those children / That keeps the word precocious

alive, / Smart but with a maturity disorder. / I was one of those children /

That thinks factoids as good as cash / At the bank of adult approval.”

“Lessons” deals in a jaded way with those awkward evenings where teacher meets

parents – but the scene it paints is very accurate. And then there is his most

self-examining poem “Palanquin” which declares: “I am one unlikely

receptacle / making space for desire… /… All mornings I wake / To the despotic

myth called me… /… I’m my secret favourite, / I am in love with my agency the

most, / My desire the most, my smoke the most, / Most my myth, most my inward

boom.” Is this about a young man growing up or simply narcissistic? Is it a

fantasy? At the very least it is about growing into oneself, even if it often

means “crawling between earth and heaven”.

The closing poem “Querent 2” has the

Tarot card reader saying she has misread her reading. She also says “I’m not

making fun. Read right and / You will kill your mother’s voice. / You will make

love to your father’s / Memory, and so be very happy.” Interpret this as

you will but note that, like the Greek Sibyl, what the card reader says could

be at best ambiguous and at worst false. It appears to be allowing the young

man to reject women and feminine ways. A rather Freudian conclusion.

There is an ongoing puzzle in this

collection. Who exactly is being interrogated or speaking in the cards? One

person or many? I admit that I find some poems in this collection to be cryptic

and often difficult to decode. Not that this deflates Arthur’s achievement.