We feature each fortnight Nicholas Reid's reviews and comments on new and recent books.

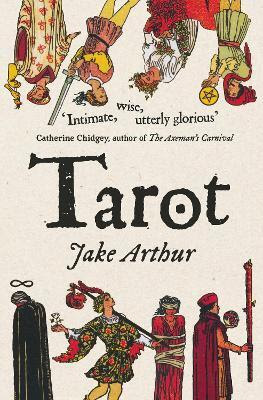

“STILL IS” by Vincent O’Sullivan (Te Herenga Waka University Press $NZ30); “IN THE HALF LIGHT OF A DYING DAY” by C. K. Stead (Auckland University Press $NZ29:99); “MEANTIME” by Majella Cullinane (Otago University Press $NZ30); “TAROT” by Jake Arthur (Te Herenga Waka University Press $NZ25)

Not by design but by happenstance, three collections on this posting refer to death – Vincent O’Sullivan’s death; the death of C.K.Stead’s wife Kay; and Magella Cullinane’s loss of her mother… and even Jake Arthur’s “Tarot” does sometimes refer to death, albeit cryptically.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

New Zealand was deprived of a great poet when Vincent O’Sullivan died, aged 86, in April of this year. (My tribute to him, Remembering VincentO’Sullivan, can be found on this blog). O’Sullivan was prolific in his poetry when he wasn’t writing short-stories, novels and non-fiction biographies. Fortunately, there was one last collection of poetry to be released posthumously, Still Is. It contains ninety poems, perhaps because O’Sullivan aspired to reach that age. As always in his collections of poetry, O’Sullivan does not organise his poems as a series of themes. His poems are presented in no particular order, and he often makes the title of a poem part of the poem itself. Given his age, there are naturally reflections on ageing, and therefore there are also poems calling back the past, including childhood and adolescence. The first three poems of Still Is consider vague remembrances of making love (old age recalled); a blind man who can find his way around (overcoming infirmity); and a refection on gates as they once were.

Reading this collection, I can’t help noticing some predominant themes and ideas.

First there is remembrance itself, tied to the idea of time and of our tendency to misremember events. The ticking of time is seen in terms of art in the poem “Randomly so, in a gallery” where “Lightens. Dark comes in. Their grace we go along with, / clocks edging season to season. / Painters as ever insisting their one belief: / the leaning of great slabbed light, dark slanting in.” The poem “Last time” begins “It was so different last time… / There were thrushes. I remember it rained / in buckets. The tarseal on the drive / crinkled in the torrent. I remember that…” and there is the persistent idea of how apparently small and apparently insignificant things can nevertheless be the most remembered things. In remembrance there is occasionally a reaching back to how forebears were presented to him when O’Sullivan was young. “Slaint” is one of the few poems that deals with O’Sullivan’s Irish ancestors while “Uninvited twin” also broods on the fortunes of the Irish who crossed the Atlantic. Inevitably, too, there are childhood memories with “Grey Lynn Noir” (just avoiding being beaten up by the local thug), “Bastards, down from the hills” (a very rough boys’ game), “Seven, yes” (little boy first understanding that “bum” is a rude word… though grown-ups use it often) and a poem or two referring to attending convent school. As for early adulthood (when O’Sullivan would have been in his twenties), the prose poem “To be fair to the Sixties” is about hippie-ish druggie-ness in the 1960s and suggesting how it was mainly pointless if not destructive.

As for old age, there are inevitably reflections on decay. “He comes to mind” considers meeting a solitary old man and how his stoicism sustains him. “Any weekday’s likely” basically tells us that all things decay. And there is a more ironic take on decay with “Catching Lenin’s ear”, about how the dictator’s preserved body is falling apart.

Speaking of extreme states of mind, we are presented in a number of poems with how the brain works. The poem “extras” is halfway between theatre and halfway a dream when under dental anaesthetic. “Premonition” combines mental fantasy with suburban unease [it’s in part about spiders];

while “As few may tell you” is an ironic account of ghosts and how people do or do not deal with them. Though O’Sullivan was ambiguous about religion, with regard to his Catholic upbringing he could be amused. He uses the title “This business of lost belief” not to tell a tale of losing religion, but to tell of missing his chances with a girl whom he admired when he was a young teenager.

His sometime quirky-ness is found in “Either isn’t or is” and “Dreamwork” both of which take cats to be arbiters of life and death – after all, silent cats do appear to be watching and judging us don’t they? In contrast “Ciao, Norman” is a brisk but heartfelt elegy for a dog that had to be put down.

These are just some of the ideas that O’Sullivan dealt with in his last collection.

His style is various. He could build vivid, if daunting, scenes, as in “A good place to buy” viz. “The winds hug at the house till the ribs crack. / The guttering swings loose as a shot arm. / The sound of shrieking’s in the splitting wood. / The violence you have to accept before spring / breaks perfect.” He could be jocular as in “Easy does it, easy” which I take to be an elderly man accepting that many things which once seemed precious or important but which now can now be shucked off. I quote it in full: “Dogs on beaches. / Books on shelves. / A single mirror / For a dozen shelves. / A toy Ned Kelly / A theorem,s proof / A spinning dolphin / On a garden’s roof. / A wall of photos / Tell a hundred years, / A funeral’s laughter / A wedding tears. / A life of veerings / You make out was straight. / Nicely polished granite / And a final date. / Like hell, we say, / Let’s start again. / The sermon’s over. / The day shines through rain.”

Then of course there is O’Sullivan’s ability as a critic. “Confessional as it gets” politely answers a reviewer who suggested he was out of steam. He confesses: “At times – yes, I need to say it - / between the sighs of the living and the vanished / departed, I’ve written jaunty numbers, / turned the wry erotic lyric, / half a dozen times I’ve persisted, / tasteless even, after dusk…” But then aren’t such poems necessary to prevent poets from becoming too solemn about their work? “A gift for drama” notes how much of human interaction as play-acting… we are like squealing mice. “No choice much, any longer” suggests there are so many writers now that the same themes are being overworked (all too true). “So at least we know” sees the broadcast evening news as usurping communal prayer as “The News an atheist’s variant / on prayer: for what the day has achieved, / forgive us; from what tomorrow intends, / preserve us; out of creation’s wreckage, / rise again.” “Life on air, for example” is a half-jocular, half-mocking of New Zealand radio.

At a certain point though, O’Sullivan accepts that though we are a special species, we are still animals. I quote in full his poem “To accept being human” thus “I give thanks we were cradled in branches, / that we moved on so surely to hands daubed in caves. / I give thanks to the dragged knuckles / and the penetrating gaze. I’d be so proud / were Silverback an ancestral name. / I watch viewers at the rail of the ape enclosure. / I’m at one with ordure accurately flung.” And he is clearly jocular about the approach of death in “Nothing too serious, mind you” and “For the obituarist”. These must surely have been written when O’Sullivan’s was aware that he was dying.

My apologies for naming and quoting so many of O’Sullivan’s poems but, believe me, I have quoted less than a third of the ninety. Certainly a man of many interests. As for the title “Still Is”, I can only see the defiance of a man who accepts that the world is as it is. There is often a bluntness in O’Sullivan’s poetry, but it is refreshing when put up against the preciosity of many poets, too eager to show off their erudition.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. * *. *. *. *. *. *. *

In a preface to In the Half Light of a Dying Day, Karl Stead, now in his 92nd year, reminds us that he had written poems inspired by Catullus in earlier collections, one being “The Clodian Songbook”. In the age of Julius Caesar, Catullus wrote many love poems – or poems of rebuke and annoyance – to a woman whom he called Lesbia. This woman is now generally understood by Latinists to have been Clodia Metelli, wife of a powerful general and official. Avoiding the name Lesbia, Stead uses the name Clodia for the alluring and fickle woman of many moods. However, in these poems Stead himself takes the role of Catullus. Catullus is a means of talking about the present as much as the past. In the second part of this collection, Stead creates a new character called Kezia, a name used in some of Katherine Mansfield’s stories. If Catullus is Karl Stead, then Kezia is Kay, Stead’s wife of seventy years, who died in July of last year. While the first part of In the Half Light of a Dying Day deals with many different ideas, the second part is focused on the drawn-out illness and final death of Kay, becoming a long and moving elegy. All these poems were written in 2023.

Part One is “The Clodian Songbook [Continued]” which begins with a general invocation, then turns to “History”, an account of the precarious times in which Catullus lived, invited to a banquet with Julius Caesar when he had written smutty poems about Caesar’s circle and could have been killed for it. But while others were killed for mocking, and Caesar himself was killed, Catullus’s main punishment was to be unknown for centuries. Catullus died when he was thirty, and only the “silence of the grave / and with the passage of so many centuries / your words and your wit would / find their way home.” With “The Farm” Stead injects New Zealand images and “Moreporks” into a story of Stead /Catullus as a boy. Kevin Ireland is addressed as the Roman poet Licinius in a “shape poem” that welcomes him as a comrade. But in another “shape poem” Stead takes a crack at James K. Baxter as “Hemi / shaggy and barefoot / he was your Diogenes / full of contempt for your wants and your wages / and with a wisdom not all his own - / traditional, Catholic / not entirely to be sneezed at / but for Catullus / retrograde / masculist / at once flashy and necromantic / belonging to a past / best left behind.” He concludes “Catullus envied your fluency / Jim / but thought you might have put it / to better use.” There are poems that seem to be aimed at an in-crowd which would not be understood by us outsiders. “Creative writing class?” appears to be about a rupture between poets, but who were they? “Uncertainty” has young Stead/Catullus at a bohemian gathering trying to guess “who among us is fucking whom”. There is an apocalyptic piece about the “World’s End”, though without being hysterical and “The good man in love” wherein Catullus pleads with the gods that he be shorn of any love for Clodia given that she was untruthful, unfaithful to him… and yet he still can’t break away from her. Now that is a theme that is brushed earlier in a version of Catullus’s famous epigram “Odi et Amo” – “I hate and I love” - still attracted to Lesbia [Clodia] but still appalled by her. [For the record, and standing outside Stead’s poetry, I note that in full Catullus’s epigram reads “Odi et amo, quare id faciam, fortasse requires? nescio, sed fieri sentio et excrucior”. The best translation I have ever seen is in James Michie’s translation of all Catullus’s work, thus “I hate and I love. If you ask me to explain / The contradiction, / I can’t, but I can feel it, and the pain / Is crucifixion.” ] How much do Stead’s Catullus poems refer to his love life? I’m in no position to know.

Part Two “Catullus and Kezia” is very personal in its presentation and therefore difficult for an outsider to discuss fairly. Stead opens with “Home”, in which old man and old woman are no longer travelling “no more travel for them…/…old age has taught them / to love what they have / this green enclave where flowers and fruit flourish / where tui and blackbird, / pigeon, sparrow and thrush / build / and teach their young to fly”. Perhaps this is an idealised version of the Steads’ Parnell home, but it leads into happy memories when husband and wife were young. “Language again” gives a [possibly] idealised version of their first love-making. But the sickness of Kay is looming.

“Modern Miracles” is an ironic title as the poem concerns the way modern airlines could whisk the Stead’s younger daughter back from London when Kay’s health was declining. Starting with the poem “Free will”, the couple do some intense thinking about their lives. Karl’s wife of seventy years says she chose to stay with him, despite all their ups and downs… They consider photos of themselves when they were young… and how her absence from public places is now being noticed by friends… and the importance of her reading. But the physical decay is relentless. The poem “Pain” considers “the gods” who are silent while Catullus / Karl tries to ease the pain of Keyzia / Kay by rubbing her back “she panting, shivering, sweating / seeming so small so shrunken and depleted / and still so loved.”… And finally in “Sorry”, the tragic moment comes when Kay dies beside Karl in their bed. “You kissed her cheek / Catullus / and told her you were sorry / and wept. / She would have wept to see you weeping / but could not / did not know they were your tears / falling on her face / did not know anything / anymore / who had known so much.”

There is the long aftermath. In “The science” he longs for, but cannot embrace, the idea that there is something after death. Then there are reveries: In “Gallia” he remembers the pleasure of being together with Kay in southern France; and Paris. There are briefer poems almost nearing the epigrams of [the real] Catullus - “The plum tree”, about life still going on when he is still alive (and now wearing a Medic Alert). With “A Beginning” he remembers when they had their first child, in the early 1960s. The poem “Now more than ever seems it rich” picks up on John Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”. Keats continues “Now more than ever seems it rich to die, / To cease upon the midnight with no pain, / While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad / In such an ecstasy! / Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain— / To thy high requiem become a sod.” Catullus recalls Kezia calling for this poem and weeping at the beauty of it… but Keats’ harsh word “sod” suggests immediately the finality of death. “The wound” appears to refer to the poet’s love life and his wife’s reaction to it. Kezia says that Catullus’s poems about Clodia “had to be written / because of your deplorable / romantic ego / and the wound it had sustained”. Of course there are other interests that intrigue – “The Story?” suggests that high culture as we know it is collapsing ; “The puzzle” has him recalling his childhood and how very different Auckland then was; “Catullus demonstrates a vulgar taste” when he watches on his own, and thoroughly enjoys, the old song-and-dance movie “Singing in the Rain” (and so he should, dammit). And inevitably “After death” is the closing poem. The final words are “in the half light of a dying day”.

I have to close with the most obvious words – the “Catullus and Kezia” sequence of this collection is by far the more engaging, and I would also suggest the more heartfelt, of the two sequences. It is a genuine elegy and it would have taken great devotion to write it.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

Back in 2018, I had the great pleasure of reviewing Majella Cullinane’s debut poetry collection Whisper of a Crow’s Wing (reviewed - all too briefly – on this blog ). Irish-born and raised but now New Zealander, Cullinane’s style was described by me thus: “It combines a romantic sensibility with a modernist sharpness.” Cullinane dealt with Irish old times and emigration and her own Irishness, all with an excellent sense of time, place and perspective. In Meantime, she has a much more testing perspective to deal with. I take the collection’s title to have a double meaning – “meantime” usually means filling in time; but here the time really is mean. When Covid 19 was shutting New Zealand down, and travel was restricted, Cullinane’s mother, far away in Ireland, was succumbing to dementia. Even by long-distance phone calls, Cullinane had great difficulty talking to her mother who became more incoherent as her dementia increased.

Cullinane charts this trying and tragic situations in three parts.

Part One “Am I still here?” begins with the poem “This is not my room” – the poet’s mother refusing to stay in the hospital that is caring for her and already confused as to whether she is still at home. The mother is also very much aware of a world beyond this earthly world – a mixture of Christianity and folklore. In “The believer” she shows her awareness of the dead [as told by the daughter]: “They’ve been calling you more of late. They, who can’t be seen or verified. / For a believer, it’s hard to ignore the dead, or that other world / most can scarcely reckon with, the one you’re so certain of.” In various poems, the mother imagines noises in the hospital. She thinks of supernatural beings. She is sure a French angel is visiting her… and she has forgotten her wedding day. But we are aware that we are seeing all this through the eyes of the daughter, far away in New Zealand. It is the daughter [the poet] who has to imagine her mother’s reactions in “If the walls could speak.” And then we come to the definitive point, “The long goodbye”: “They call what’s happening the long goodbye - / the disease that each day snatches parts of you / and scatters them about, until you can’t find them, / until you don’t remember losing them.” This is the painful process which every carer knows – the time when it is clear, in the patient’s loss of memory and inability to do routine things, that dementia is irreversible.

Part Two “Meantime” has the daughter coping with her mother’s death and also her sense of guilt that she has not been able to attend her mother’s funeral. When the mother has lost communication, the daughter delves back to childhood and the family’s rituals. The poem “The wedding ring” reads in full “My sister removed your grandmother’s wedding ring, gripped / your calloused palm, took your cold hand in hers, / the same hands that held us, the arthritic fingers / that once kneaded bread, the long fingers that never glided / across a piano keyboard, never strummed the strings of a guitar.” “Virtual funeral” forces the daughter having to guess what her mother’s funeral was like, as she is torn by her absence on the other side of the world: “On the morning of your burial, it’s late evening here. / Everyone’s in bed, the house is quiet. / I’m in the sitting room, lying on the couch / waiting for the call from my sister. / She tells me she feels better now that you are safe.” In

“Meantime” she still has a sense of guilt for her absence “I would compress seas and oceans, turn hemispheres upside down / to believe what has happened has not happened…. /… I try not to think of you in the spring-churned earth, far away so cold in there so cold.” She creates poetry inspired by Dante, especially “Make no sound” has her questioning “why are we in purgatory? Wasn’t her mind purged enough?”. She experiences the huge sense of loss as she sees momentarily a woman looking like her deceased mother.

Part Three “Nowhere to be” finally brings some sorts of closure. There is in this last section, the long-term regret, remembering mother (and father in the poem “Widower”) and their Irish home… even if the poet is triggered by things she sees in New Zealand. She has many dreams of her mother, now seen in her mind as younger than she was in the end. The daughter remembers in detail some of her mother’s skills, such as making bread. The poem “All Souls” is halfway to belief in the traditional All Souls (remembrance of the dead); and “Something to say” has the poet, who rejected her mother’s beliefs and religion, now understanding their power more. “Stay here” has her calmed by nature, by walks… and all the time wishing her mother was with her: “Could I tell you the cat followed me to the shops / but I didn’t notice until I met her on the train tracks / as I was coming home? You would have laughed. / Could I tell you I wish you could see this sky? / We could sit on the deck. / Ignore the overgrown clematis – I’m not much of a gardener. / I wish I could speak to you / but I don’t understand the language of the dead.” In a sort of coda, she visits the Old Country and says goodbye to her mother’s grave.

I apologise for this half-baked excuse for a review. As you will have noticed, all I have done is to give you an account of Majella Cullinane’s ordeal, presented in three segments – mother’s infirmity and mental decline ; mother’s collapse and death ; daughter’s regrets and conciliation with memories and the present. What I have not dwelt on is the clarity of Majella Cullinane’s style. Regrettably, clarity is a rare virtue in much current poetry. Cullinane’s style is lyrical when it has to be, straightforward when it has to be, and always fully aware that there are many different but valid ways of embracing this world and what might be beyond it. Meantime hangs together as one coherent statement and proves Cullinane’s outstanding skill as a poet.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

Last year (2023) Jake Arthur produced a brilliant debut with a collection of poetry called A Lack of GoodSons (reviewed on this blog). It dealt with many psychological states, often referring to chronic mental discomfort. Though mainly written in the first person, it was not necessarily confessional. Arthur’s new collection Tarot often deals with some of these same ideas, but the approach is very different. The opening quotes Hamlet: “What should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven?” - which is virtually a cry of despair, a man’s horror at the state of things and the crushing littleness of the self.

This time, the conceit (presented in the opening poem “Querent 1”) is that a Tarot reader is reading the cards to a callow listener who is apparently male. Given the Tarot cards, there is in what follows much symbolism, the imagery sometimes tending to the medieval. The title of every poem is connected to a Tarot image - “Knight of Swords”, “Seven of Cups”, “The Wand” etc. I do not know how seriously Jake Arthur takes the Tarot, but it is at least a framework in which conditions and states of mind can be examined. And one idea that is examined frequently is the nature of the sexes, and the friction between male and female. Male and female both speak through the cards. “The Spell” appears to be concerned with ambiguity about sex or gender. “His Mien” begins “No accounting her taste / For hangdog men, weak / of chin and short of smiles, / Not so much brooding as broken, / And if he’s good in the bedroom / No one wants to imagine it.” This is at least a sad perspective on ageing, but it introduces the idea of women as domineering. “Rest and Recreation” has a dominant woman sexually using a man and having somewhat patronising ideas about him. In “Play-time” a distraught woman appears to be planning arson.

Is this misogyny? Probably not, for these poems could also be read legitimately as a young male groping to understand the nature of women. And there are some poems, such as “Mater familias”, in which a mother is celebrated, even if in a wry way. “Her Caller” and “Salt” appear to be childhood memories.

As for the male, there is much admiration. “Lost bantam”, the longest poem in the collection, begins as a story of being shipwrecked and washed ashore on a desert island, but morphs into a tale of gay desire. “Goose” is the most overtly gay poem in the collection, while “Tagus”, a poem about Alexander the Great, suggests masculine comradeship which is much more than just virile.

It’s important to note that while Jake Arthur is concerned with the sexes, he also has many other interests. “Life Hack”, pessimistic in the face of ecological collapse, he suggests it might be best for us to get used to it and again lived simply as our mediaeval peasant ancestors did. “Re-gifted” is perhaps the most desperate poem, about an over-intelligent kid who grows up to find his intelligence means nothing. Grown up, the kid says “I was one of those children / That keeps the word precocious alive, / Smart but with a maturity disorder. / I was one of those children / That thinks factoids as good as cash / At the bank of adult approval.” “Lessons” deals in a jaded way with those awkward evenings where teacher meets parents – but the scene it paints is very accurate. And then there is his most self-examining poem “Palanquin” which declares: “I am one unlikely receptacle / making space for desire… /… All mornings I wake / To the despotic myth called me… /… I’m my secret favourite, / I am in love with my agency the most, / My desire the most, my smoke the most, / Most my myth, most my inward boom.” Is this about a young man growing up or simply narcissistic? Is it a fantasy? At the very least it is about growing into oneself, even if it often means “crawling between earth and heaven”.

The closing poem “Querent 2” has the Tarot card reader saying she has misread her reading. She also says “I’m not making fun. Read right and / You will kill your mother’s voice. / You will make love to your father’s / Memory, and so be very happy.” Interpret this as you will but note that, like the Greek Sibyl, what the card reader says could be at best ambiguous and at worst false. It appears to be allowing the young man to reject women and feminine ways. A rather Freudian conclusion.

There is an ongoing puzzle in this collection. Who exactly is being interrogated or speaking in the cards? One person or many? I admit that I find some poems in this collection to be cryptic and often difficult to decode. Not that this deflates Arthur’s achievement.

No comments:

Post a Comment