We feature each fortnight Nicholas Reid's reviews and comments on new and recent books.

“NIGHT SCHOOL” by Michael Steven (Otago University Press, $NZ25) ; “THE PISTILS” by Janet Charman (Otago University Press, $NZ25) ; “TUNUI / COMET” by Robert Sullivan (Auckland University Press, $NZ19:99; "SEASONS" by William Direen (South Indies Press, $NZ22); "ANOMALIA' by Cadence Chung (We Are Babies Press, $NZ25);“EVERYONE IS EVERYONE EXCEPT YOU” by Jordan Hamel (Dead Bird Books, $NZ30)

I would not for one moment question Michael Steven’s skill as a poet. He has a strong sense of style and – perhaps unusual for one of his generation - he is very much committed to more traditional stanzaic forms. His sequence “The Picture of Doctor Freud” consists of six loose sonnets - or at least six 14-line stanzas. “Dropped Pin: Trinity Wharf, Tauranga” takes the same “sonnet” form, as does his concluding sequence “Intercity Bus Elegies”. The sequence “Winter Conditions” comprises five poems in 12-line form. As for all the other of the 33 poems that make up Night School, they are presented in orderly stanzas, sitting like square bricks on the page. Steven composes methodically, corralling all his ideas carefully, even if those ideas are often inconclusive or even despairing.

I admit straight off that up till now I’ve not examined Steven’s work closely enough. When I reviewed on this blog his debut collection Walking to Jutland Street (2018) my comments were regrettably brief, though I was interested in the hard, non-nostalgic view he gave of remembered student digs. I appreciated more his second collection The Lifers (2020), on the whole a chilly and dark view of New Zealand, with much reference to criminality, but redeemed by poems of compassion and showing a broader view of humanity. Now comes Night School, and I’m torn by the thought that we have to take much of it as autobiographical. At least I think we are. How can you critique a man’s confessions? A dilemma for a reviewer.

The title Night School is ironical – there are some poems about attending a literal night school, but the “night” part also suggests the darkness in which criminality happens and young men are “schooled” in the worst habits of society. Night School may very well be called a sequel to The Lifers. Once again, Steven introduces us to “Dropped pins” meaning always a poem giving close scrutiny to a particular locality with a personal memory. The opening proem “Dropped Pin: Symonds Street, Auckland” puts us in very much the same milieu as did much of The Lifers – gathering of old friends, one clearly living off petty crime and his life going nowhere. There are eleven “dropped pins” in Night School, carrying Steven over much of New Zealand, although Auckland and Christchurch are most often visited.

Two dominant themes run through this collection. One has to do with families and fatherhood and their failures. We have to assume that “The Picture of Doctor Freud” is autobiographical. Steven does insert a little social satire, telling us of his father “He kept us fed in a world of sharks / while suited pig-hunter economists / filleted the country with Bowie knives.” But the sequence becomes a very dark reflection on the sexual life of his grandfather and on his own first adolescent experience of the opposite sex. Also presumably autobiographical, “A Methodist Family Portrait” suggests family violence and the over-disciplined life imposed on his great-grandfather, with a hint that such warped upbringing persisted in the family tree. “The Gold Plains” might begin as a sunset scene, but morphs into a suggestion of an unfulfilled life, especially in terms of fatherhood . Looking back at the sunset, he sees “Somewhere nearby would be the father, / sitting alone in his inherited silence / unable to name the emptiness inside him, / the same emptiness his father endured / before him and was unable to name.” “Dropped Pin: Trinity Wharf, Tauranga” gives a dyspeptic take on Tauranga (the seedy criminal side of it) but segues into memories of a broken home. As for personal background, “Dropped Pin: Addington, Christchurch” is one of his bleakest memories of younger years working in a factory.

The other dominant theme is, of course, drugs. “Strains: White Widow” is a reminiscence of dope-smoking youth. “Papa Jacks” goes into harder drugs. Poems like “Two Wolves” would put you off hard drugs permanently as would “Dropped Pin: Kingsland, Auckland”, but I’m not sure if this was Steven’s intention. There are poems about different strains of weed, the longest being “Strains: Slurricane”; while “The Secret History of Nike Air Max” tells us that wearing this cushioned footwear provided the necessary stealth and silence when pilfering drugs from pharmacies. Steven makes some literary references, though some of them are presented in doped-out form as in the ones on Charles Spear (sort of) and Ronald Hugh Morrieson. There are, it must be added, some poems dedicated to fellow poets, others to people unknown to most.

In the end, what attitude is Steven adopting? Is he presenting illicit drugs as simply a way of life in NZ? Or is he offering a critique and regretting a drug-messed youth? There are definitely moments where he hints that a less delinquent life might have been desirable. Take “Winter Conditions” which takes a drive through the outer suburbs of Auckland. At first it seems to satirise “square” lives, but then it undercuts itself with the idea that rebellious younger attitudes might have been bogus. Thus: “Most would blindly follow an inherited model:/ careers, mortgages, the trappings of respectability. / That wasn’t for me. I could never roll like that. / What I sought was a kind of psychic repatriation, / some way of harmonising with the ineffable. / Nihilism was chic in the decade we came up in.” Don’t tell me that the underlined part isn’t mocking such perceptions. A similar give-and-take is found in “Animal Kingdom” about being in a prison van and its contents. The title itself subverts the ostensible reportage. “Dropped Pin: Eastern Beach, East Auckland” seems at first to be building up as a schoolboyish ironical critique of a schoolteacher but in the last lines redeems the man.

Steven’s envoi “Intercity Bus Elegies” is violent and gripping in its profuse imagery, but it comes across as less apocalyptic then disoriented –a generic condemnation of us all. Everything is for the worst and God is either absent or transformed into the rage of a doped-up ranter.

As an Aucklander who also travels much in the Waikato, I read dropped pins about Pigeon Mountain, and Symonds Street and Eastern Beach and East Waikato, but I can only conclude that Steven’s experiences of these places are radically different from my own.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

In terms of style, Janet Charman, in her ninth collection of poetry, makes an extreme contrast with the orderly stanzas of Michael Steven. I remember reading with pleasure Charman’s At the White Coast (2012) and reviewing it for Poetry New Zealand, later designating it as “a loose autobiographical collection written in free verse”. The same could be said of her 2017 collection [Ren] Surrender, reviewed on this blog. Charman apparently always composes in free verse, far from the world of carefully-crafted stanzas. She also follows the now-somewhat-dated preciosity of rarely using capital letters. The first-person-singular “I” always has to be rendered as “i”, because “I” is too phallocentric for this poet, an abominable sign of male dominance and toxic masculinity.

The Pistils is not what I have sometimes called a “concept album” – the type of poetry collection structured around one dominant theme. Rather, as in earlier collections by Charman, it is a collection on very diverse topics and often refreshingly so.

Her opening gambit “high days and holy days” (I’ll stick with lower case for her titles) is a sequence of twelve statements, sometimes a little flippant and/or dismissive about certain public holidays, only occasionally rejoicing. She writes poems about gardens showing that they are hard work and sometimes lamenting the destruction of gardens when new owners take over an old house-and-garden. Perhaps inevitably for somebody in her late sixties, there are poems that recall childhood. “when i was young” makes ironical comment on how differently safety for children is now taken in contrast with the old days. There are reminiscences of the awfulness of schooltime cookery classes and how going to see the panto was like, and was not like, going to church. She lingers on the topic of adults caring for children and the constraints these often impose. Inevitably too, there are poems about ageing, with presumably autobiographical accounts of declining health. “going west” is a generic elegy for the departed. “gracious living” refers to varicose veins, while both “bra dollars” and “clickety-click” introduce a masectomy.

In all this, what we are aware of is Charman’s feminism. Poems, sometimes a little cryptic in expression and larded with mythological references, laud the female body, its gestation and resilience. Read “the gold zipper” and “because desiring” to see what I mean. The title poem “the pistils” has clearly Sapphic overtones, but is rather muddled as are many of Charman’s statements when she goes grandiose. Pistils are the “female” organs of the flower that produce seeds and fruit and the poem therefore assumes the powerful creativity of women - hence the cover image of a flower. (A different sort of pistil is encountered in the poem “October garden”). The sequence “thirteen bystanders” speaks of women’s empathy and ability to socialise harmoniously.

However, Charman’s feminism can too easily turn into toxic femininity and snarling misandry as in “My Mister”, though it is hard to make out (so badly is it written) what she is or is not endorsing about the sexes in “womb”. “the holy ghost and the lost boys” is a mash-up of different mythologies again suggesting the redundancy of men. She also takes a pot-shot at James K. Baxter in “The House of the Talking Cat” (note the capital letters for these phallocentric guys) in which he refers to raping his wife. I think we already knew about Jim’s many ethical shortcomings. Oh yeah. There are also the poems where Charman shows how daring she can be. In “selfie” her assessment of her own body includes peeing. “the holy ghost and the lost boys” has “cunts” in it and – gosh, we’re so stunned and impressed - there’s a poem called “cunt”.

Taken as a whole, The Pistils is an uneven work.“Telethon”, one of her longer poems, regrettably reveals her weaknesses as a poet. With a few decorations, it is essentially a first-person account of the anxiety and eventual relief in having a baby cared-for in hospital… but as poetry it trundles along as a narrative which would better have been presented in pure prose. This is also a case where the absence of conventional punctuation simply creates confusion or at least mystification about something straightforward. Yet by contrast, “classroom” is equally discursive, manages to create a vivid and totally believable scene of primary education as it was. There are lots of ups and downs in this collection.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *.

Oh for the joy of jumping into something both heartfelt and skilled!! Robert Sullivan’s Tunui / Comet comes with endorsements by David Eggleton and Ruby Solly; and the blurb describes it as” “A marvellous hikoi through Aotearoa today alongside a leading Maori poet”. A bit excessive, maybe, but a reasonable signpost to the contents.

Sullivan, says a publicity handout, is Ngapuhi / Kai Tahu. But genealogically he’s more than that. He also has Pakeha ancestors. This fact he references in a number of his poems. The sequence “Decolonisation Wiki Entries” acknowledge European ancestors and the section of the sequence “Ruapekapeka” mentions a Pakeha ancestor who fought on the British side during the New Zealand Wars.

This is not a trivial point, as he considers much of the history of Aotearoa with an ironical impartiality.

Of course there are stabs at colonialism.

The poem “I wasn’t a poet for writing placenames” purloins the voice of James Cook, who is made to say: “dance’s oil painting stitched me / in a wig with my dress uniform / gold buttoned in some map room / pointing at Australia / yet I could’ve been / dressed for fifty shades of grey / with my fine curls a cut above / bloody run barrels and other / bligh whipping tales about / by severed burial at sea” The “fifty shades of grey” bit sounds like a silly cheap shot, but the poem attacks the pomposity of much imperial historiography. The stupid comments tourists make about Maori sites are chastised in “Rock Art.” Yet when he gets to Parihaka in the brief poem “Feathers”, he quotes both Pakeha and Maori perceptions. The poem “Ah” is slightly ambiguous but is not condemnatory of James Cook’s arrival and what he brought, while “Cooking with gas”, imagines a James Cook who reconsiders his approach to the Pacific and, as well as bringing good things here, wonders if he could have found a more peaceable and conciliatory way of intervening. Sullivan’s sequence “Te Whitianga a Kupe” celebrates both Kupe and Cook. The 8-part sequence “Te Tahuhu Nui” is interesting in that its first section has verses beginning with quotations from Kupe, then examining how his relatives relate to these statements in the way they now recall and discuss things; but later parts of the sequence has him recalling his distant Pakeha ancestors (apparently mainly Scots).

Can I say that Sullivan is a realist? Deeply committed to Maori culture and its perpetuation, he is also aware that this country was made as it is by more than one people.

In all this, let me not underestimate Sullivan’s knowledge of Maori lore and foundational stories. “Maui’s Mission”, one of the first and most attractive of his poems, gives a lyrical account of the fabulous raising of the fish and “Homage to Te Whatanui” elaborates on another. Most poems in this collection are in English (as Sullivan says at one point, the language he was raised speaking) but some are bilingual. There are two poems completely in Maori. Please note, too, that Sullivan is also aware of the contemporary urban scene. One of his jauntiest poems “Hello Great North Road” connects central Auckland with fishing and surfing out on the city’s west coast, and gives the sense of something actually lived.

Some criticisms? As you can see in a quotation above, Sullivan sometimes has the lower-case infection (no capital letters) I’ve noted in another poet in this posting. Sullivan can also sometimes be prosey. “Our Powhiri for the International Students” and “Conservation” are straight prose statements. Even worse “H.G. Wells’” which reads thus “If only I could move forward ten years / in a time machine, bring the family with me / enjoying the government’s successful / reshaping of the education sector / where education is strongly linked / to wellbeing outcomes for all.” It sounds like a-letter-to-the-editor, or a boosting political pamphlet.

But I am nit-picking here. Tunui / Comet is a robust, readable and honest collection and a great pleasure to read.

*. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *. *

High praise for the smaller presses that produce poetry away from the mainstream of university presses. William (Bill) Direen, resident of Otago, produces Seasons via South Indies Press. I assume that “indies” means independent presses. Seasons presents an almost Thoreauvian statement. But not quite. Direen is not an uncritical observer of nature and into his poetry he inserts the hard shards of reality. Seasons is a poetic diary tracing the turnings of the seasons from autumn to autumn. In a strath an hour’s drive from Dunedin, Direen observes not only the seasons but also the local customs and history. (Yes, not being a Scot I had to look up the word “strath” in the OED and discovered it means a “broad mountain valley”.)

This tracing of a year begins with images of desolation and dereliction: “Lacking its rear wall, / the house makes an unintended loggia. / Starlings have strawed the attic. / Dust and cack covers the joists.” There is midday fog and the dourness of the season. Ditches flood and the town pump fails. But there are also unexpected pleasures in autumn “Late season plums are ripening at their rate, / willow happy birds are eager and sweetened. / Teeth have torn apricot flesh from stone. / When the work is done / we will know apples’ wholeness.”

Then comes full winter. There is a fire alarm and a house burns down. A blind boy plays the piano. There is a wedding. An “eradicator” comes to get rid of a nest of wasps. The contemplation of the stars fuels strange dreams and some mystic conclusions. But we are not gathered into fantasy. There is also hard reality to contend with: “a stand of pines, / their creviced bark dark with moisture. They are waiting for the chainsaw, nothing nobler.” And “A willow is a playground, / a home and a roaming ground. / Birds carol from favourite boughs, / they seek sucking mites that turn leaves red. / Rats sneak around its base…”. Late in the collection there is an awareness of the uncertainty of events, the folly of assuming that history is a neat arrow (“it is always time / to prepare for the worst”). Examples are given of local familial disasters.

Direen, then, is not merely rhapsodising on nature, but giving a sense of community and its mores.

Do I have any criticisms of his work? Just a few. He does have a tendency to make grandiose statements, as in “We plant seedlings and conserve. / We reduce hard matter and destroy species. / we are lights of simultaneous extinction, / season after season.” Also, I find a forced antiquity in some of his vocabulary, as in lines like “the Southwest is gathering / to benight the sublunary”. Gosh. And, possibly my fault for being a townie who lives far from Otago, I did have to once again resort to the OED to decipher some words. “Summer has ceased its thripping” he writes. How many would know that “thrips” are insects injurious to plants? Or that “myriapods” are centipedes and millipedes, and a “shoat” is a very young pig?

In this I am quibbling. Direen’s descriptions are vivid, if often dour, and Seasons carries the commendable weight of things closely observed.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

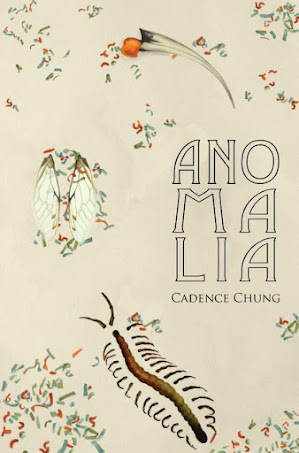

Cadence Chung’s Anomalia comes from another independent press “We Are Babies”, founded by young women and dedicated to publishing the works of women. How ironic the press’s name is meant to be I do not know, but it is focused on youth. The blurb tells me that the poems making up Anomalia were written by Cadence Chung in her last year at high school. Nothing to be sniffy about that. History tells us many great poetic talents flourished first in their adolescent years – Chatterton, Rimbaud, Dylan Thomas, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath – so why not celebrate another teenage poet?

And, in terms of poetic form, Cadence Chung is an accomplished poet. She tries, successfully, many forms of poetry – free verse; unpunctuated blocks of prose poems; orderly traditional stanzas; poems with cancelled lines; and list poems. The list poem “table of contents”, corralling diverse old things together, is almost a piece of fond nostalgia.

Like others, Chung also writes without majuscules, which occasionally makes for uncertain punctuation. Interestingly, she does not focus on her Chinese ethnicity – I think there is only one brief reference to ethnicity in this collection. Two strains of imagery dominate Anomalia. One is vivisection and the other is youthful desire. In poem after poem, cold vivisection is pitted against living flesh, be it human or animal, and their conflict is never resolved.

The opening poem “abstract” is somewhat ambiguous in meaning. At first it seems to be protesting against vivisection and cold scientific calculation, but it then adopts a more cynical tone about what human behaviour is anyway. Is this irony… or adolescent bravado? The poem “warning note” again uses the imagery of vivisection, but in this case it is purely metaphoric – it is the verbal and physical “vivisection” that a man practises on a young woman as he tries to seduce her. He is, in effect, mentally trying to strip her apart. This depressing scene contrasts with another image Chung is keen on, the flowers with their sexual organs blatantly on display. Botanical nature does not use devious stratagems to mate. Later, “notes for new recruits” brings in the image of vivisection when two girls sleeping together are – again metaphorically - wrenched apart by cold implements. And thus it continues in “the specimen to the scientist” and “the scientist’s notes” and “the scientist to the specimen". Chung observes closely species that fall apart naturally, as in her frequent references to cicadas losing their exoskeletons. Their living disintegration is nature’s form of vivisection. Elsewhere, with images of killing spiders, and verdant fields “damp and mushy… slick with ants”, Chung is never rhapsodising nature.

Yet in the poem “anatomy”, there is featured a “dandelion fluff” which radiates a very human desire for love or at least recognition “trying to find / a home somewhere, a place to seed / and stay, all i want is for someone / to divide me into neat parts and lay / them all out, so i can see / the pesky veins that cause my blood / to swim, the blushing heart that / tries to love more than it can chew through”.

What, in the end, does all the imagery of vivisection and desire amount to? Sorry to play Dr. Freud, but I find it hard not to relate it to the adolescent’s first serious attempts to measure the world; to try to work out his or her place in the world. Fitting together the broken pieces left by vivisection relates to a search for identity; and the desire is, again like most adolescent thoughts on the subject, really a desire that is not yet fulfilled. It is interesting that Chung references the kokako’s mournful cry in the bush and the kakapo’s boom – both of them suggesting a desolate loneliness. Here stands the young person looking somehow for love. “rise” comes closest to being a love poem, but draws back with a wariness about other people. Similarly in “the anomaly’s love poem” there is a wish for love but a wariness about being diminished by it and categorised by a potential lover. Categorisation is also found in “curio cabinet” while “home” aches with desire for family and friends. Full adulthood is not yet here, and there is intense self-consciousness, especially in the poem “magnus opus” which seems built on acute adolescent fear of how other people are assessing you. I am not being dismissive when I say that many of Chung’s assertions and images suggest an intelligent adolescent trying to define herself, most apparent in the poem “what I want” where each line ends “give me”; and even more in “boy scout” where “i wanna be told of my merit / to hold it in my hands / i wanna be told i deserve the world / and that everything is out here for me to discover.” And “i want” turns up again and again in the poem “belated wishes”.

I have no intention of being condescending. Cadence Chung has a great talent and skill with words. If she has the outlook of a sophisticated adolescent, she has the perceptive intelligence of an adult. I’d say just the same about Rimbaud, Thomas, Plath and the gang.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

And a third book from an independent press, Dead Bird Books, Jordan Hamil’s Everyone is Everyone Except You.

I found it very hard to engage with this collection. Okay the author is a relatively young man. But, regardless of what three over-enthusiastic “critics” say on the back cover, Everyone is Everyone Except You is so drenched in self-pity that sounds like a whiney fourteen-year-old’s view of the world. Crawl your way through it and you find the standard whinges. Decaying masculinity rusts in a shed; families break up but don’t want to talk about it; influence by, and simultaneous revulsion from, religious education; a poem “Good kiwi lad” telling us of repressed gayness; “God doesn’t watch you anymore” seems to be essentially about masturbation guilt. Yep, we really are into pubescent angst, folks.

The self-pity ramps up when we have sections headed “Everyone is having sex and meaningful relationships except you” and ”Everyone will succeed in their endeavours except you.” The final poem in the book “Human Resource” gathers together all Hamel’s declared negativities. True, there are attempts to be ironic about it, as in “The Jordan Hamel Committee of Failed Relationships” which basically says I’m a loser and will continue to be so. And of course there’s a lot of specific sex talk, typical of those who have just found out a few things about sex.

The reverse of the self-pity coin is, of course, grandiose day-dreaming. Consider “I’m falling in and out of love” which includes the lines “I want / strangers who meet me in passing at parties / to decide upon request / that yes they would die / to save me from a minor inconvenience”. Perilously close to death-bed fantasies, this belongs to an age-group even younger than a whiney fourteen-year-old.

I found only a couple of poems in this collection that almost meant something: “We are the happiest couple at the party” at least includes a comical string of improbable situations; and “When you take the Netflix account with you” verges on valid satire.

The blurb tells me that Jordan Hamel was at one time a Poetry Slam champion. It figures. Slam events feature the same barrage of semi-coherent statements which might seem interesting when heard in live performance, but come across as inane on the printed page.